[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Give Me Liberty ]

Major Players

Give Me Liberty

For more on our hero Nathaniel, please see sections Finding the Story and Fifers: the Littlest Soldiers. For Moses, the Battle of Great Bridge.

The old schoolmaster Basil Wilkinson, one of my all-time favorite characters, is an archetype of people so important to colonial society and its youth—but almost invisible in history books. Basil’s life story was inspired by the journal of John Harrower, an indentured tutor from Scotland, and Philip Fithian, tutor to Robert Carter's children on the Northern Neck. Such schoolmasters were wondrously diverse educators, versed in music, visual art, dance, and the classics. Many could also perform music for gatherings or do a little bit of bookkeeping to earn enough wages to survive. A good number were “traveling” teachers, riding a circuit from estate to estate.

Basil’s personality, however, is entirely his own doing. Buoyant, gawky, and kind, Basil grew into an enthusiastic mouthpiece for the Age of Enlightenment, its delight in learning, the new, completely radical notion that the common man was just as capable as the noble-born to think, to reason, and to decide his own fate. My children (now adult creative artists) have always been my first readers and best editors. Basil definitely became more endearing in his quirkiness and excitability over the power of words and ideas because of hearing my then 11-year-old son laughing fondly at his antics when reading passages featuring the idealistic, sweet-natured old man.

Basil saves Nathaniel from an abusive employer, buying out the remaining time on his indenture—which costs the schoolmaster all the cash he’s saved. He takes Nathanial with him to Williamsburg and the home of a carriage-maker I name Edan Maguire, whom Basil knows is in need of an extra hand and where he himself lodges in exchange for teaching the mistress of the house how to play the spinet.

Edan’s circumstances are based on the real-life carriage maker favored by the royal governor, Lord Dunmore: Elkanah Deane. I’d found Mr. Deane by skimming ads running in the 1772-75 Virginia Gazette, looking for the arrival of ships carrying indentured servants into Leedstown, to find a tradesman who truly purchased their 7-year term of servitude (you can access the Virginia Gazette through Colonial Williamsburg’s research library). Deane ran ads offering rewards for the capture or information about his runaway indentured servant John Hunter and a journeyman named Obadjah Puryer.

He also placed notices about his riding chairs, phaetons, and carriages with intricate descriptions of what they looked like. He advertised that he had rooms to rent, fine liquors for sale, and that his wife would take orders for stays. He got into a bit of a tit-for-tat with a competitor who slurred him as “the Palace Street Puffer.” It seems pretty clear that Deane could be an ill-tempered taskmaster.

Even so, Deane’s fate made me think more sympathetically about the plight of one third of colonists who remained loyal to the crown, mostly because their family was back in England. Deane had followed Lord Dunmore from New York to Williamsburg, purchasing a lavish house on Palace Green, thinking his association with the governor would guarantee him a prosperous business. It did the opposite. He quickly careened toward bankruptcy as orders for his beautiful carriages dried up in the embargos of any product related to British rule. As hostilities grew, Deane’s ads requesting payment progressed from respectful to anxious to desperate.

The other important member of that carriage shop was Nathaniel’s gregarious and indomitable friend, Ben Blyth, an ardent patriot teenager, apprenticed to Edan Maguire when his country gentry family fell into financial disaster. Ben grew from snippets of information about the rebellious activities of Williamsburg youth. He is almost as important as Basil in coaxing Nathaniel out of his timidity, born of many losses and abuses.

Visitors to Colonial Williamsburg will know about the Royal British marines stealing the gunpowder from the town's octagonal magazine. I wrote what I thought a fairly powerful mob scene after that theft, but I still needed something to make that watershed moment—the catalyst for many Williamsburg residents to finally turn patriot—more personal and specific to Ben and Nathaniel. It came with a lesser-known incident on Whitsunday 1775. According to the Gazette, after commandeering all its gunpowder, the British marines secretly left a booby trap spring gun tied to the door of the magazine. When several teens, caught up in patriotic zeal, decide to raid the magazine to get whatever muskets the British raiders might have left behind, the gun exploded, peppering them with swan shot, badly hurting one of the youths. The only participant named in the newspaper was Beverly Dixon, who may have been the mayor's son. The injured boy is not identified, so I felt safe letting Ben assume his reality. A reality that would infuriate Basil and prompt the elderly schoolmaster to join the newly forming 2nd Virginia Regiment. Nathaniel follows him as a fifer.

When researching the Battle of Great Bridge, I discovered that a 19-year-old John Marshall fought in it with the Culpeper Minutemen—an important, less-discussed “founding father” to legitimately include in my narrative! Marshall would go on to serve in Congress and briefly as secretary of state before becoming the 4th Chief Justice of the United States. Marshall is the jurist credited with consolidating and defining the Supreme Court’s role in our federal checks-and-balances system. His majority opinion in Marbury v. Madison was the first to declare an act of Congress unconstitutional, establishing the power of judicial review in our government.

Marshall grew up in what then was the frontier, in Virginia’s Fauquier County at the base of the Blue Ridge. The eldest of 15 children, young John was largely self-educated through readings suggested by tutors like Basil. Tall and athletic, he was known for having a convivial nature, hearty laugh, an optimistic faith in the good of common man, and an impressive ability to negotiate squabbles, likely born of being a big brother to so many siblings! All of which prompted me to include him as an additional mentor to Nathaniel, especially during a scene revolving around a large ethical choice Nathaniel has to make. Alexander Pope was evidently Marshall’s favorite author. So, I let him drop quotes from Pope’s Essay on Man during campfire chats, as a way to tuck in little pearls of Age of Enlightenment philosophy without the dreaded “info dump.”

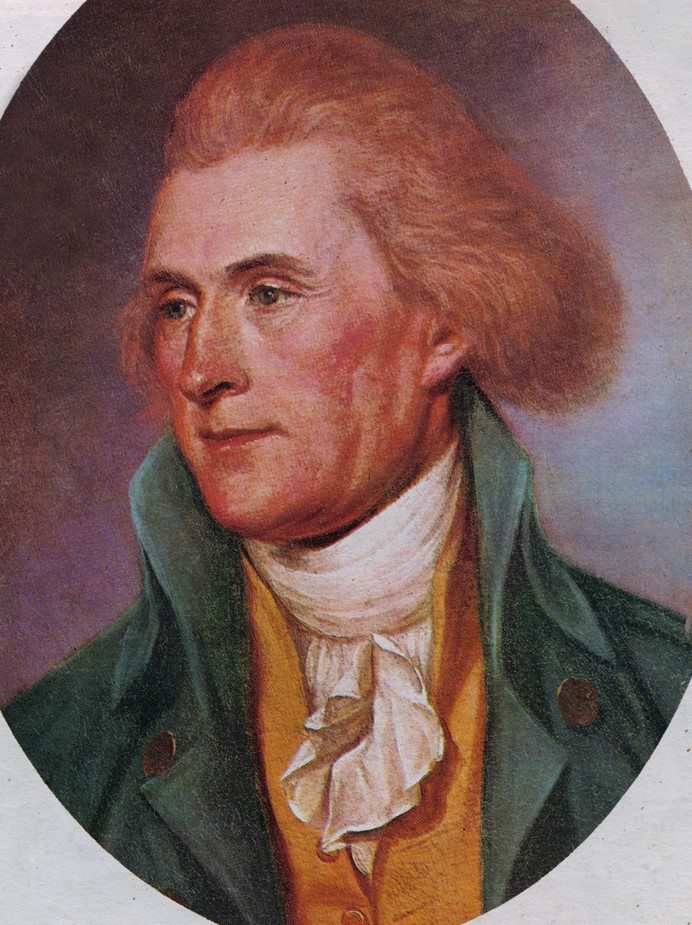

By the way, I won’t include real persons in my narrative unless they truly were there at the same place and time as my main character. So, when George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, or Peyton Randolph appear in Nathaniel’s story, I knew from newspapers and documents that they truly were walking the streets of Williamsburg that day. Then whatever comes out of their mouths better be plausible, true to who they were. Whenever I can, I use actual quotes in their dialogue.

One such scene I had great fun writing was an exchange between Nathaniel and TJ. I promise their conversation is entirely in keeping with what we know about Jefferson. The scene involves his horse running away, his precious violin tucked in the saddle bag. Jefferson was not only a lawyer, architect, writer, horticulturalist, and musician, he also liked to dabble in horse breeding for racing. Which is how he ended up with a rather over-spirited horse. I won't spoil the scene but will say TJ is exceedingly relieved to have his violin returned to him. Legend has it he won his wife’s heart with his violin playing.

Music was also a poignant bond with his cousin, John Randolph, a prominent loyalist and the brother of Peyton Randolph, patriot Speaker of the House of Burgesses and first president of the Continental Congress. The three are a heart-rending illustration of how much of a civil war our Revolution was, often pitting brothers, cousins, neighbors against one another. (That is also a feature in my other Revolutionary War book, the bio-novel, Hamilton and Peggy!) When fighting broke out, loyalist John had to flee Virginia for England. But he left his violin behind in Williamsburg for his cousin Thomas Jefferson, with a note “in remembrance of better times.” The two had often played duets together as they grew up. After he died, per his request, John Randolph’s body was carried back to Virginia, the land he grew up in and loved. He is buried beside his patriot brother Peyton in the chapel of the College of William and Mary.

Finally, Nathaniel has a bit of a teenage crush on Maria, the daughter of Clementina Rind, Virginia’s first female printer. In 1774—two years before the Declaration of Independence and when most people in the colonies were angry at the King’s taxes but still staunchly loyal to England—she had the guts to publish Thomas Jefferson’s A Summary View of the Rights of British America when other printers refused to. Drafted as instructions to the Virginia delegates going to the First Continental Congress, TJ’s tract was a resounding list of grievances against Parliament and King George, a precursor to the declaration we all know and celebrate on the 4th of July. In her early 30s with four young sons and daughter Maria to care for, Clementina took over leadership of Williamsburg’s Virginia Gazette at the death of her husband—without missing a single issue of their four page Thursday weekly.

Please see my blog post about her for more on her inspiring proto-feminist life.