[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Give Me Liberty ]

The Battle of Great Bridge & Its Soldiers

Give Me Liberty

I am embarrassed to say as a lifelong Virginian that until I started researching Nathaniel’s story, I did not know about the Battle of Great Bridge—a brief but critical skirmish in December 1775, just outside Norfolk, which honestly may have saved the Revolution from dying before it even completely began.

Here the Chesapeake Bay opens onto the Atlantic Ocean. (It’s a vulnerable back door to so much of our East Coast, BTW, making it a prime target throughout our history for attack from pirates and the British in the 18th century to Hitler’s U-boats in WWII.)

Reacting to the growing rebellious disgruntlement of colonists and their support of the Boston Tea Party with their own “non-importation agreement” of British tea, Virginia’s royal governor, Lord Dunmore, had seized Williamsburg’s store of munitions and gunpowder and amassed a sizable fleet. He had so terrorized the towns and farms along the York and James rivers with those ships that a regiment of patriot volunteers had “turned-coat” and renamed themselves the Queen's Own Loyalists. The aldermen and mayor of Norfolk, out of terror of bombardment, had signed loyalty oaths and were wearing sprigs of red on their coats to signify their obedience to the crown.

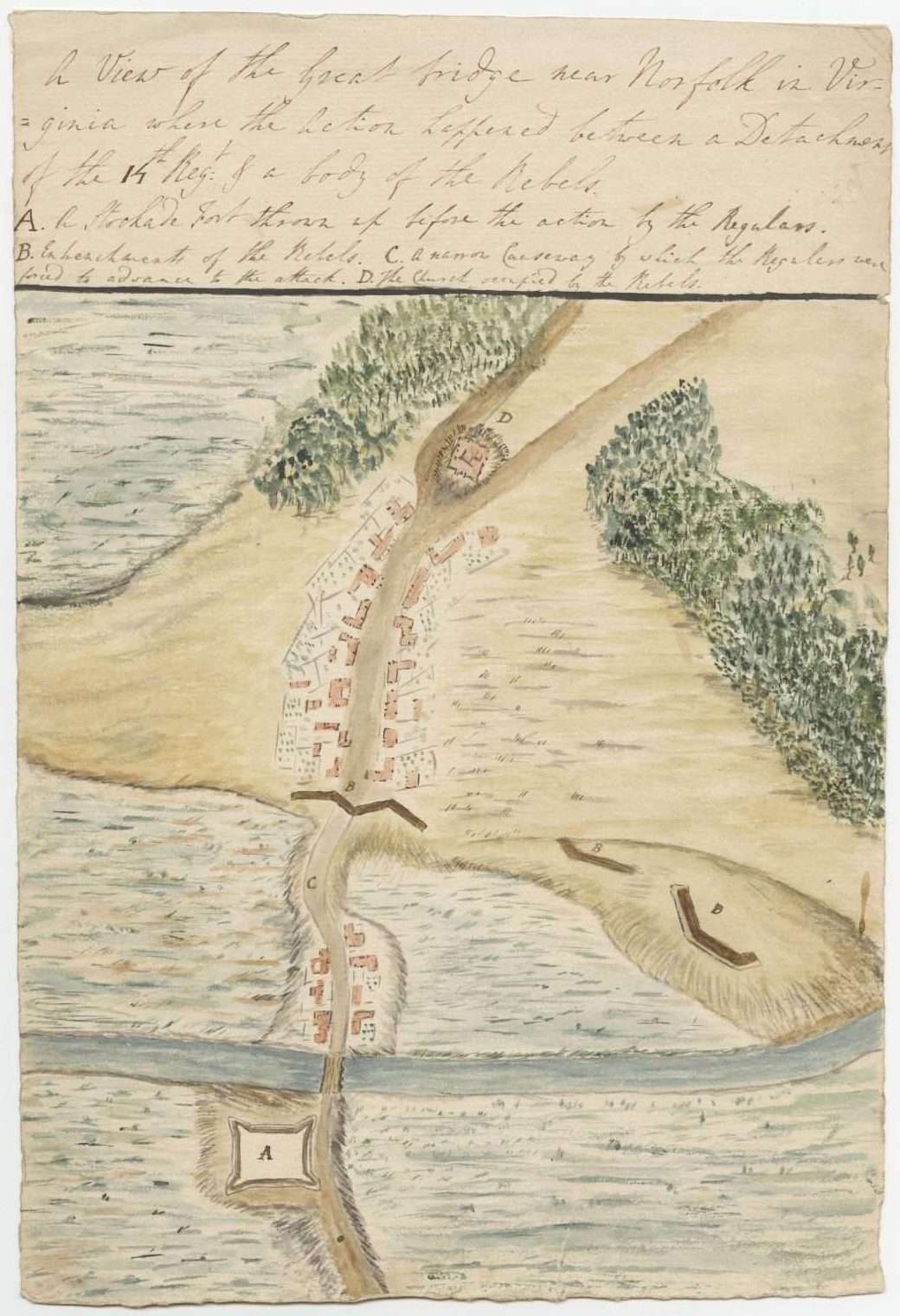

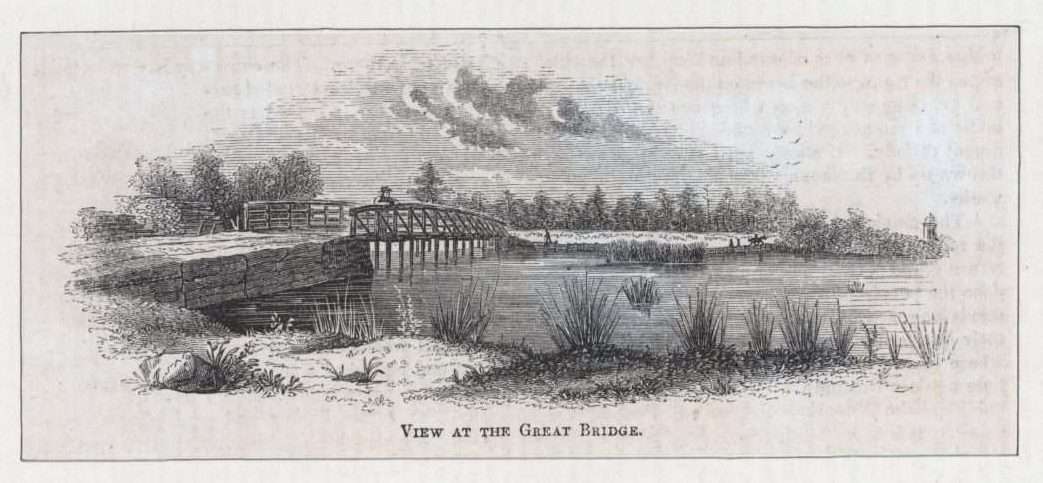

Fourteen miles south—in the middle of the Dismal Swamp—along the one road connecting North Carolina to Norfolk, was one of the few bridges in Virginia at the time. Timber, pitch, and tar—all things necessary to build ships—were brought up that dirt road to the port of Norfolk. So, Dunmore erected a tiny fort to maintain the British grip on the bridge plus Norfolk and its shipping.

Until an untrained, little band of recent volunteers marched out of Williamsburg to uproot them.

Had the British won this battle, Dunmore could have blockaded Norfolk and bottled up the Bay all the way north to Baltimore. Remember goods traveled mostly by water those days. A blockaded Bay would have meant no replacement troops or supplies from Virginia or Maryland could have been sailed out the Bay and then up the coast to General Washington and the Continental Army fighting in New York.

But in typical empire arrogance, when they spotted the small American contingent approaching their fortifications on December 9th, 1775, the British grenadiers marched across that 40-yard-long, 8-foot-wide bridge in lockstep, six men abreast—completely exposing themselves like bowling pins to the Minutemen and militia hiding behind trees and the outpost’s buildings. Untrained, ordinary citizen-soldiers, very young and very old, with Patrick Henry's rallying words: Liberty or Death stitched into their homespun hunting shirts. In twenty minutes, it was over—the first American victory in battle, no matter how small or quick. And within a few weeks, Dunmore left Virginia waters altogether.

A great climax ending scene for a book, right?

Within the facts of that battle, I also discovered the Royal Ethiopian—a regiment of runaway slaves who fought at Great Bridge, not for the Americans, but for the Redcoats. By order of Lord Dunmore—in a proclamation that urged enslaved servants to escape and join the British in exchange for their freedom—those who fled bondage by patriots were enlisted. Those who fled loyalists, however, were, sickeningly, returned to them in chains.

The Royal Ethiopian mocked the Patrick Henry slogan Americans had stitched onto their shirts by wearing a sash with Liberty to Slaves. When I read that detail, the visual image of that horrible juxtaposition amid the smoke of musket fire knocked the wind out of me a bit. That terrible and tragic irony insisted I create two characters with opposing storylines—a runaway slave with the Ethiopians, who would face off with a beloved friend fighting with the patriots. (Educators, when students complain about research, reassure them that's where you discover compelling, humanizing story.)

So, that one little battle provided me with an ending, two main characters, an important moral dilemma, and the thematic spine of my novel—how people had to seek liberty in different, dangerous, sometimes heartbreaking and, for way too many, disappointing ways. It even suggested a double-edged title. For our young hero, Nathaniel, the plea of Give Me Liberty ultimately redeems, redefines, and liberates him. Toward the end of the book, when granted his freedom from indentured servitude, he asks carefully to reassure himself of the reality of it: “Free to make my own choices? Free to make my own coming and going?” It was an unheard of, turn-the-world-upside-down mindset in a time when all of Europe was ruled by kings. Nathaniel recognizes that agency as the life-altering gift it is and that’s when he finds his courage to join the patriot cause.

Conversely, his dear friend, the enslaved runaway Moses cries out in despair when he and Nathaniel stumble onto one another as enemies in battle: “You fighting for people who whine for their own liberty and keep me in chains?” A question that we are still answering, a promise we are still working toward today—liberty and justice for all, and a government of, by, and for the people.

To learn more:

Great Bridge Battlefield and Waterways Museum—(opened 5 years after Give Me Liberty was published. I’d have loved to tap into their resources when writing!)

Also:

https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/the-battle-of-great-bridge/

https://www.jyfmuseums.org/learn/research-and-collections/essays/what-was-the-battle-of-great-bridge

The Royal Ethiopian Regiment at Great Bridge:

https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/lord-dunmores-ethiopian-regiment/

https://www.explorehistorycnu.org/2024/02/22/the-ethiopian-regiment-and-the-fight-for-independence/