Laura's Blog

Happy Birthday, Leonardo da Vinci!

April 15, 2016

Today, April 15, 2016, is the 564th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci birth. It’s also our dreaded tax day and as a historical fiction writer I can actually celebrate the otherwise onerous day because it is through tax records (and land deeds, baptismal records, and diaries) that we learn the skeletal details of people’s lives during historical times. Thanks to tax records, we know, for instance, that Ginevra de’ Benci’s family was the 2nd richest clan in Florence, only behind the Medici in wealth. That told me a lot about her circumstances and her potential mindset and intellectual/poetic hopes.

With Leonardo, we can track the milestones of his life through tax records. But first his birth….

Leonardo was the illegitimate son of Ser Piero da Vinci, a notary of some social standing in the little town of Vinci (da Vinci simply means “from Vinci”). His mother’s name was Caterina, and for a long time she was described as being a local peasant. But scholars now believe that she might have been a Turkish slave in Piero’s household, brought from Constantinople. Documents found in Vinci support the theory, as does a fingerprint Leonardo left on one of his paintings. The central whorl matches a common pattern found in people of Middle Eastern descent.

While illegitimacy would restrict Leonardo in some ways legally, a “love child” was not uncommon or hidden during the Renaissance. Leonardo’s grandfather made note of his birth in his diary, writing: “1452. There was born to me a grandson, the son of Ser Piero my son, on the 15th day of April, a Saturday, at the 3rd hour of the night. He bears the name Lionardo (sic).” Hours of the night were timed from sundown, so Leonardo came into this world probably between 10 and 11 PM.

His grandfather also recorded his baptism and the names of ten godparents—all present at the church service. Clearly, Leonardo’s birth was a celebrated one with that many godparents present!

Scholars believe Leonardo spent his earliest years with his mother in the house pictured here. It is a sun-washed cottage, atop a hill that spills down into the valley, today filled with sweet-smelling olive groves. Standing there, it is easy to envision a chortling, rambunctious toddler and young boy, climbing trees and watching with fascination birds coasting the winds below him. Surely Leonardo’s lifelong fascination with flight started here.

Click here to see video footage of Leonardo's childhood home: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w8ImCwnu8mM&feature=youtu.be

Eight months after his birth, his father married a woman named Albiera, who was the daughter of a successful Florentine notary. Notaries were mini-lawyers of the day, drawing up contracts, wills, and deeds. The “Ser” in front of Piero’s name is an honorary title given to respected members of the community. Albiera was of high enough social rank that their marriage may have been arranged for a long time, even as Caterina gave birth to Leonardo. Albiera’s family connections brought Piero important business opportunities in Florence, 28 miles away.

When Leonardo was a little over a year old, Caterina married a producer of lime named Accatabriga. Together they would have five children.

In 1457, when Leonardo was five-years-old, tax records show his grandfather listing him as a dependent (earning himself a 200 florins tax exemption). We don’t know for sure if Leonardo actually lived with his grandfather, but Antonio must have been involved in his day-to-day life.

The adult man who had the greatest interest and emotional investment in Leonardo was his uncle Francesco. Francesco was only 15-years-old when Leonardo was born and did not have a profession, playing the role of the country gentleman, supported by the family’s farms and other land holdings. Legend has it the two spent a great deal of time wandering the Tuscan countryside together. From Francesco, Leonardo grew to love horses and nature. When Francesco died, he left his entire estate to his favorite nephew.

Leonardo’s illegitimacy barred him from most professions (such as being a notary) and from receiving a humanistic, literary grammar school education, where he would have learned Latin—the language in which most intellectual treatises, poems, and essays would have been written. He would spend his life struggling to learn it on his own.

Instead, he received the shorter, practical schooling designed for tradesmen—arithmetic and reading in the Tuscan vernacular. The 16th century biographer Vasari would write that Leonardo plagued his math teacher with questions! We can only imagine how hard it must have been to keep the attention of a boy who could grow up to become one of the world’s most prolific and visionary inventors and mechanical/robotics engineers!

Early on Leonardo amazed people with his interest in science and experimentation. While still a very young boy, Leonardo began dissecting dead bats, lizards, and newts. According to Vasari, Leonardo startled his father by decorating a buckler, (a circular shield), with dismembered and reassembled body parts of snakes, crickets, and bats to create a dragon-like creature that would have “the same effect as once did the head of Medusa.” (Greek myth held that the goddess of wisdom and war, Pallas/Athena, carried into battle a shield decorated with Medusa’s head, turning her enemies to stone.) Leonardo’s rendition was “most horrible and terrifying,” according to Vassari, seeming to “belch forth venom from its open throat, fire from its eyes, and smoke from its nostrils.

His father sold it for 100 ducats.

In 1464, after twelve years of marriage, Ser Piero’s wife died in childbirth. They had no offspring, and within a year, Leonardo’s father married again, Francesca Lanfredini, the daughter of an affluent notary in Florence. Piero moved to the city, taking a house on the corner of Piazza della Signoria.

It was a year of upheaval in Florence. Cosimo de’ Medici—who had nurtured so many artists and funded the building of the Duomo’s astounding dome—died, leaving a void in leadership in a city run by deal-making, argumentative merchants. His son Piero did not have the same political savvy. There were many assassination and coup attempts against him, until finally he died of gout and his son, Lorenzo the Magnificent, rose to power at the tender age of twenty. Lorenzo would fuel the city’s artistic and philosophic Renaissance and use cultural diplomacy to negotiate peace among Italy’s warring city-states. Hence his being called by adoring Florentines Il Magnifico.

This was the Florence Leonardo entered when he was an adolescent. In 1466 his father apprenticed him to the great Andrea del Verrocchio, a goldsmith, engineer, painter, and preeminent sculptor, who had succeeded Donatello as the city’s foremost creator of statuary. His studio, or bottega, was the busiest in the city, nurturing many artists including Botticelli, Perugino, Lorenzo di Credi, and Ghirlandaio (who would later train Michelangelo).

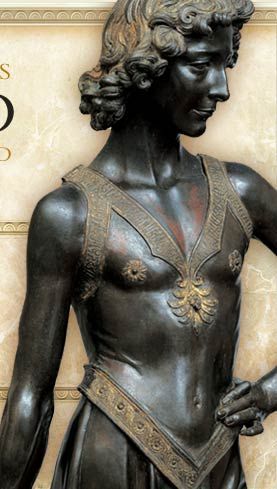

Verrocchio was a favorite of the Medici, who commissioned many pieces from him, including a David. It is thought that a preteen Leonardo posed for it. The sweet, gentle face in this statue may offer us the only likeness of a young Leonardo. It certainly bears a resemblance to what scholars speculate is a chalk portrait of the artist as an old man by one of his students.

More on Verrocchio and Leonardo’s time in his bottega in my next blog for our Leo-week!

Tonight we’ll be celebrating Leonardo’s birthday at One More Page Bookstore in Arlington. http://www.onemorepagebooks.com/. Come join us!

Leonardo probably would not have celebrated his own birthday. Although Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans seemed to have feted one another on their birthdays, Christian doctrine found it too egotistical and even pagan to do so. That didn’t stop the nobility from throwing themselves parties (which may be where the tradition of birthday “crowns” came from.) But birthday parties for more ordinary folk really started only in the early 19th century with the German kinderfeste and the advent of free standing cookstoves.Leonardo was also relatively unusual in the exact date of his birth being recorded. Most of his contemporaries might know the date of their baptism, and if they celebrated anything, it would have been the feast day of their patron saint, chosen at baptism.

So we’ll just have to make up for that for Leonardo tonight, 7 PM!

Other Blog Posts

Click Here to See All of Laura's Blog Posts