Laura's Blog

Political Turning Points: The Bonus Army & FDR

July 28, 2025

I’ve been writing a lot recently about the echoes and lessons of history, mostly in 1973 as presented in TRUTH, LIES, AND THE QUESTIONS IN BETWEEN (Watergate and the ERA) and the blacklisting and censorship of the 1950s’ Red Scare (SUSPECT RED). All so pertinent to now.

Today, I take you back to the Great Depression and the anniversary of a troubling moment in how our presidents and government treat our veterans—that ironically became a pivotal breaking point and impetus for more supportive and humane governance. A moment I learned about accidentally, I must admit, while researching backstory for a minor but important character in BEA AND THE NEW DEAL HORSE—Malachi.

A big challenge and goal in writing authentic fiction set in American history is facing the thorny issue of racism—presenting its terrible realities and tragic ramifications truthfully while still creating characters of color with agency within those awful constraints and prejudices. A definite issue and objective for a narrative set on horse farm in rural Virginia in the 1930s.

After looking at the Library of Virginia’s extraordinary digital exhibit of the commonwealth’s Black WWI veterans, I knew I could legitimately make Malachi one of the many brave Black soldiers who served on Europe’s front lines. Some, like the 369th Regiment, known as the Harlem Hellfighters, were assigned to the French Army in April 1918, fighting in harrowing battles such as the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. 170 of them received France’s much honored Croix de Guerre medal for bravery.

While reading a very colloquial history of Middleburg/Upperville to get some era-rich details of daily life in the region, I spotted a paragraph describing 1932’s “Bonus Army” marching through Middleburg—men from as far west as Ohio, heading to Washington, D.C. along Rt. 50. These veterans were hoping to lobby Congress for a bonus promised them as “adjusted compensation” for income they’d lost during WWI— $1.25 for each day served—to be sent them in 1945. However, given the Depression’s devastation, the veterans desperately needed that money then, when one of four Americans had no income whatsoever, not even odd jobs.

The “Bonus Army” was a stunning model of integration and joint acceptance in a time of instituted segregation and bigotry. An estimated 25,000 veterans—white and Black—from across the nation, marched together to Washington, D.C. They might have fought the war in segregated units, but in 1932 they walked the hundreds of miles to the Capitol as one. Malachi, Mrs. Scott, and Bea witness a contingent of the Bonus marchers coming through town (which also allowed me to slip in some back story about Virginia’s Black WWI veterans).

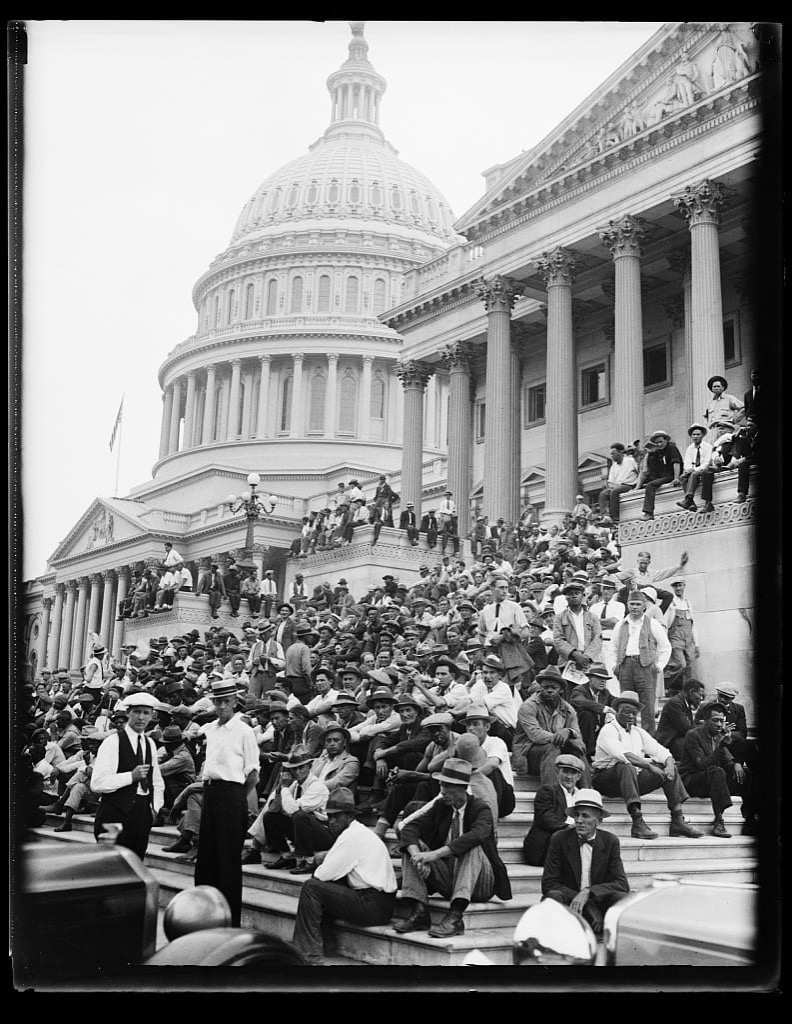

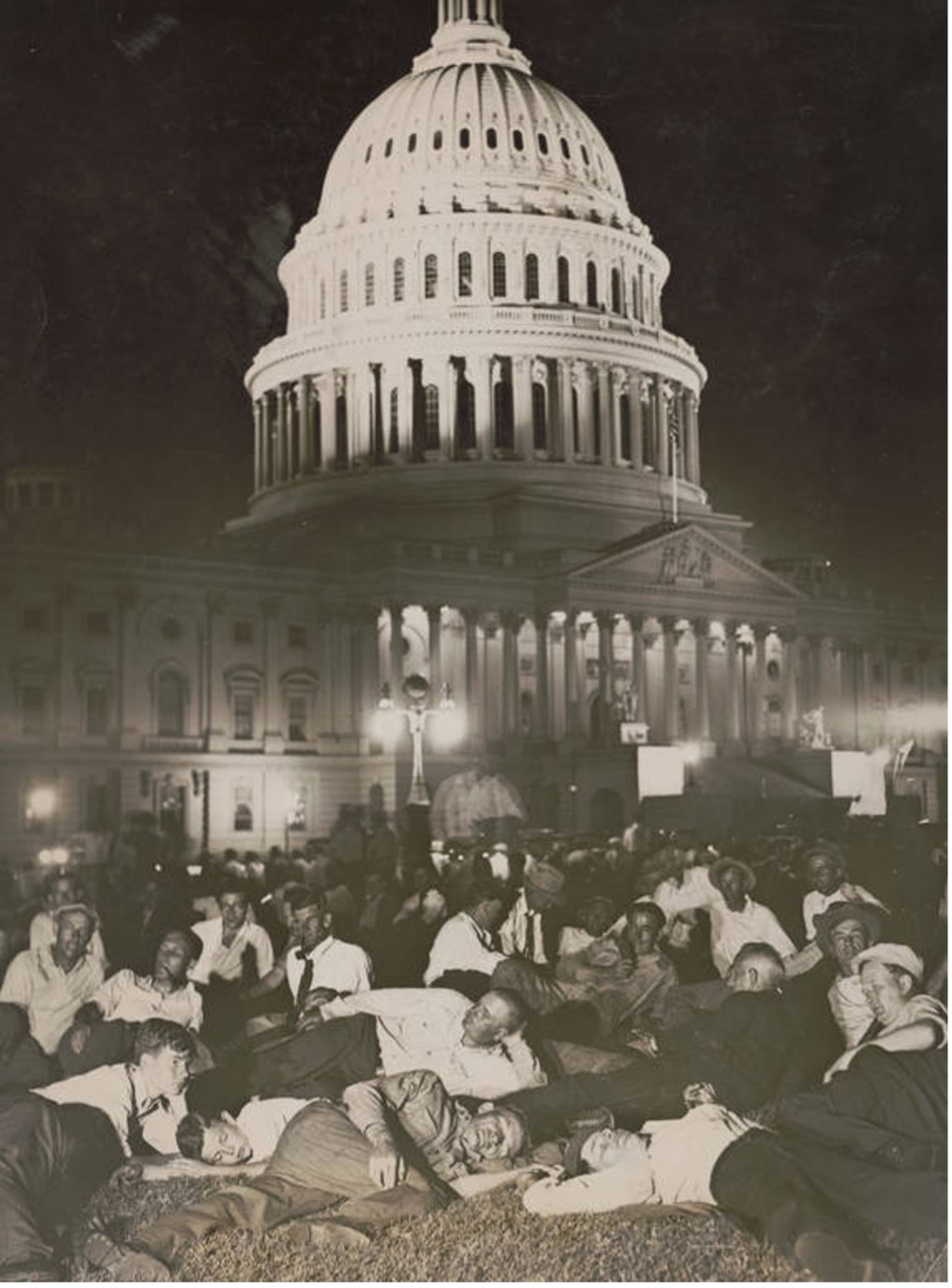

Patriotic and hopeful, the Bonus Army massed and kept vigil by the Capitol as Congress deliberated, many bringing their children along to witness history.

They camped in nearby Anacostia, creating an impressively organized mini-town of tents and quickly built cabins. They divided it into small streets named for states. The Salvation Army ran a library in its midst for them. Each night, the veterans and their families gathered for music—gospel, blues, country, popular—Blacks and whites listening and performing together. Visitors were astonished by the two races peacefully and happily sharing billets, chores, and rations.

Local authorities and the regular Army, however, saw the veterans’ growing numbers and integrated cooperation as threatening, motivated by “subversive,” socialist or communist ideology—“Red agitators.”

The House passed the bill. But two days later, the Senate voted it down—its members vacating the chamber and then the city in the dark of the night to avoid facing veterans who were quietly standing post outside, waiting for what they were sure would be Senators’ approval of the bonus. Despite their disappointment, the veterans peacefully dispersed from their vigil outside the Capitol, singing, “America, the Beautiful.” They returned to their Anacostia encampment, planning to remain in their “Hooverville” and continue lobbying. Many had no homes left to return to at that point, having lost everything to foreclosures.

Authorities began looking for any excuse to oust them. After DC police tried to clear out some veterans from vacant downtown buildings, shooting and killing two who resisted, Hoover ordered the U.S. Army to run the rest out of town.

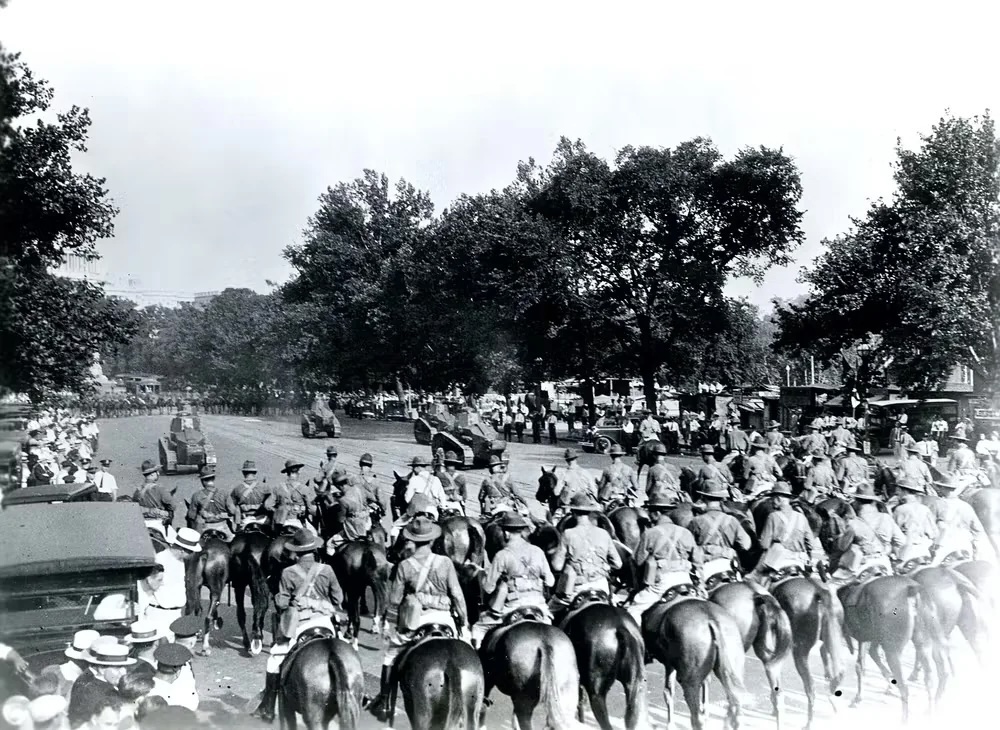

On July 28th, 1932, two soon-to-be WWII heroes—Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur and calvary officer George Patton—spearheaded the campaign, mobilizing several cavalry units, four companies of infantry, a machine gun squadron, and six tanks against fellow soldiers and their families. Patton told his cavalry: “If you must fire, do a good job. A few casualties become martyrs, a large number an object lesson...When a mob starts to move, keep it on the run...use a bayonet to encourage its retreat. If they are running, a few good wounds in the buttocks will encourage them. If they resist, they must be killed.”

Marching along Pennsylvania Avenue, the Army brandished bayonets and lobbed tear gas when they came across veterans trying to stand their ground. It also set fire to the Anacostia tent city, destroying what little belongings the veterans still possessed.

Two veterans died in the assault. Because of the gas, an 11-week-old baby died and an 8-year-old boy was partially blinded. A thousand veterans also suffered gas-related injuries. In the blaze, a rail-thin veteran from New Jersey named Joe Angelo, a private who’d been Patton's orderly and saved his life on a battlefield in France in 1918, rushed forward to implored Patton to stop the attack. Patton cast him aside, saying to aides: “I do not know this man. Take him away and under no circumstances permit him to return.”

The next day, the New York Times ran an article with the headline: "A Cavalry Major Evicts Veteran Who Saved His Life in Battle." Americans were appalled. For many, this cruelty was the last straw in the Hoover administration’s disregard for the plight of the average American during the Depression’s economic armageddon.

They turned their attention to an eloquent but obscure Democrat, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was conducting a whistle-stop train campaign across the nation, promising a “New Deal for the American people” and “action now.” Hoover’s callousness catapulted FDR to the national political stage.

That fall, when he accepted his party’s nomination, Roosevelt said: “The greatest tribute that I can pay to my countrymen is that in these days of crushing want, there persists an orderly and hopeful spirit on the part of our people who have suffered so much. To fail to offer them a new chance is not only to betray their hopes but to misunderstand their patience...Statesmanship and vision, my friends, require relief to all at the same time...Let us use common sense and business sense...in so doing, employment can be given to a million...This nation is not merely a nation of independence, but it is, if we are to survive, bound to be a Nation of Interdependence—town and city, North and South, East and West...Let us all here assembled constitute ourselves prophets of a new order of competence and of courage.”

Other Blog Posts

Click Here to See All of Laura's Blog Posts