[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Suspect Red ]

How Much Is True?

Suspect Red

My two families—Richard’s and Vladimir’s—are fictional. But the Bradleys and Whites—and their encounters with historical figures—are totally plausible, imagined amalgamations gleaned from careful research into the Red Scare and its hunt for hidden communists within America. As such, they are symbolic of people caught up in the firestorm and pressures of the McCarthy era, providing a look at how national anxieties, fear-mongering, hate-speech, distrust of foreigners, bully politics, and unsubstantiated accusations can seep into the hearts and minds of ordinary citizens and change how we treat one another. The novel’s tagline sums up the pervasive question of the 1950s: when the nation is scared, who do you believe?

As any good historical fiction writer should—especially for teenagers and young adults—I spend months and months researching before writing a word. Then my job is to fashion a compelling, human narrative laced with revealing details and historical events that allow readers to learn a great deal about that period without realizing it—through literary osmosis. With SUSPECT RED, the political aspects of the Cold War and McCarthyism are so complex I realized that trying to simply thread them through the day-to-day lives of teenagers might make too thick of a tapestry or for overly wordy dialogue. So I decided to present historic events in a way most American families would have experienced them—in news accounts—which also allow readers to encounter them, on their own, unfiltered, as did Richard.

Each chapter in SUSPECT RED begins with actual photos and news accounts of that month’s factual events, starting with the execution of the Rosenbergs for espionage, June 1953. The novel follows a year in the life of Richard, a high-schooler whose father works for the FBI. It opens with his Mom fearfully taking Robin Hood away from him since the book was banned from some public libraries for promoting “un-American,” “subversive,” and potentially Communist messages. Yes, hard to believe Robin Hood could be interpreted that way, but the Merry Men took from the rich to give to the poor—a supposed proletariat or socialist concept. Members of McCarthy’s committee staff did indeed oversee pulling what they felt were controversial books off the shelves of our embassy libraries and in some cases had them burned. Often out of fear of losing their jobs and under pressure from ideologues in their own communities, librarians across the nation followed suit and packed away “questionable” books.

In creating my protagonist, I chose to focus on two groups of citizens particularly affected by McCarthyism—law enforcement officers mandated to investigate suspected Communists and the diplomatic corps of the State Department—the very agency Senator McCarthy claimed was riddled with closet commies, sympathizers, and “fellow travelers” looking to undermine America or the “bleeding hearts” who couldn’t recognize a foreign threat. What would happen if the two worlds collided—could two teenage boys be friends despite those opposing mindsets?

Richard, the book-loving son of an FBI agent, who feels starved for similarly smart peers, meets Vladimir, a hip, jazz-playing boy whose mother is Czech and whose father is a career foreign service officer, formerly posted in Czechoslovakia, a nation recently turned communist. As the teenagers write songs together, discuss their favorite books, deal with school bullies, and play on the basketball team, Richard begins to wonder if Vlad's family might have ties to the "Reds" in Eastern Europe. He has to decide between his loyalty to his father—a WWII veteran and patriot as well as a G-man—or his newfound friend, who has so expanded the shy Richard’s world.

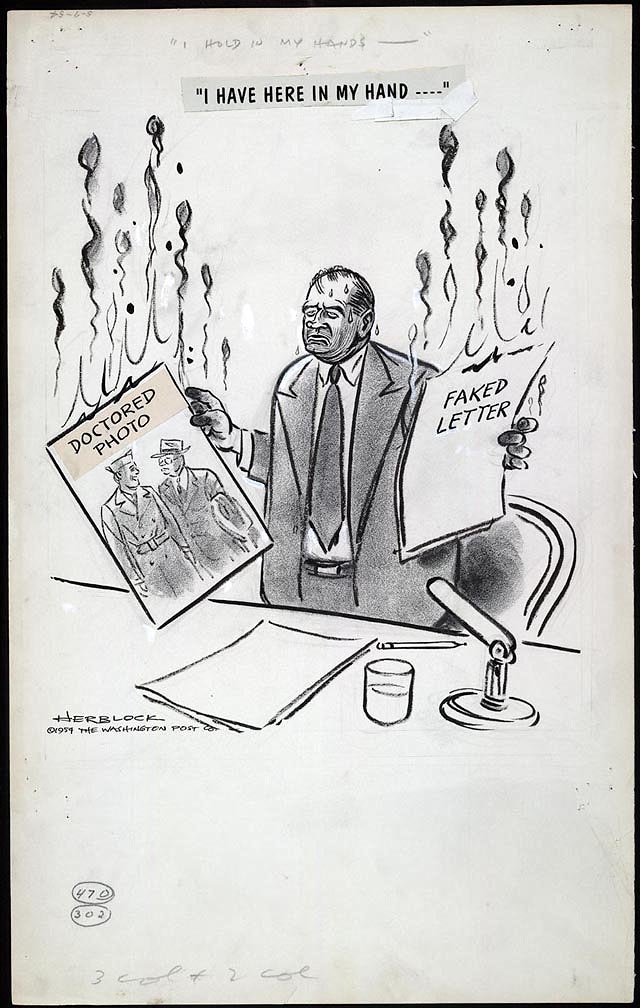

Targeting the State Department was the way Senator McCarthy rose to national celebrity in February 1950, during a speech to the Republican Women’s Club of Wheeling, West Virginia. The senator held up a piece of paper and brayed, “I have here in my hand a list of two hundred five—a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party, and who, nevertheless, are still working and shaping policy in the State Department.”

McCarthy’s accusation that our diplomatic corps was riddled with Communists came fast on the heels of the sensationalized trial of a former State Department official, Alger Hiss. He had been convicted of perjuring himself when he denied passing top-secret reports to a Soviet spy ring during World War II. Hiss had first been identified by Elizabeth Bentley, a double agent who had named approximately 150 Americans as spying for the Soviets, including 37 federal employees.

Elements of the Hiss trial read like pulp fiction. For instance, a Time magazine editor and confessed courier for the Soviets testified that Hiss had hidden strips of microfilm containing State Department documents stuffed inside pumpkins for him to pick up. The documents were linked to Hiss because of a quirk in type that would only occur from a malfunctioning key—like one found on his personal typewriter.

In the same month, physicist Klaus Fuchs confessed to spying for the Soviets while he worked on the Manhattan Project developing the U.S. atom bomb. And by early summer, the Rosenbergs would be arrested—eventually convicted of handing the Soviets our nuclear technology and executed.

Understandably, the country was jittery.

The piece of paper McCarthy waved in front of that West Virginia audience was hooey, to use a 1950s term. Within days, he himself would backtrack, first claiming he’d left the list of 205 names in his other suitcase when journalists asked for clarification. Under scrutiny by the press, he reduced the number to 81, then to 57, and finally only specifically targeted four people. A Senate committee formed to investigate McCarthy’s claims also exonerated the State Department. The Herblock political cartoon to the right refers to a photo that McCarthy’s staff cropped and a letter they may have falsified or even made up—both presented as evidence during their hearings against the United States Army for supposedly being slow to search out and purge “Reds” and sympathizers in its ranks.

Despite the press exposing McCarthy’s claims against the State Department to be exaggerated and often false, recent events had primed the United States for hysteria. (See War: Cold and Korean for more historical/geopolitical context.) McCarthyism—a term we still use today for unsubstantiated accusations used to attack people’s character and to suppress political opposition—was born.

Across the nation and across professions, rules were adopted to require employees to sign loyalty oaths. Review boards investigated employees’ opinions, behaviors, and their private lives and friendships. Civilian watchdog groups mushroomed and coordinated letter writing campaigns against “un- American” influences. Both public and secret “blacklists” were circulating warning employers, particularly in the entertainment industry, not to hire anyone named on them or anyone who defended them.

Meanwhile, McCarthy called hundreds of people before his Senate subcommittee. Often his accusations were nothing more than “guilt by association,” e.g., knowing Communists or attending social events sponsored by groups his staff suspected to be “Red” or “pinko,” leaning sympathetically toward “Red.” Sometimes suspicions revolved around nothing more than having friends, family, or interest in Russia and Eastern Europe, its culture and arts.

The total effects of McCarthyism in terms of breeding fear and suspicion, ruining careers and friendships, are hard to tangibly measure. But historians estimate 12,000 people lost their jobs. The loyalty oaths and security reviews that ensued would harm a wide range of Americans—from the 300 screenwriters, directors, and actors blacklisted by Hollywood to the 3,000 sailors and longshoremen fired from cargo ships and docks. The damage lingered for years. An anthropology professor who lost her university post after McCarthy smeared her was unable to find another teaching job for eight years.

Typically, the only way for a witness to save his or her reputation was to “name names,” to identify others who might have dabbled in Communist or left-wing politics. If they refused to do so, they might be cited for contempt of Congress or dubbed “Fifth Amendment Communists” for taking their constitutional rights against self-incrimination. With that label, McCarthy effectively discredited their loyalty to the United States and insinuated they were Reds. Thousands of people lost their jobs, and had trouble finding employment for years afterward.

Please see Links to Learning More for more in-depth information about Senator Joseph McCarthy, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, and the broadcast journalist, Edward R. Murrow, whose reporting on McCarthy began the dismantling of the senator’s hold on the American psyche.

While writing Suspect Red, I was struck by the relentless power of rumor and our human tendency to assume someone is guilty of something if his friends or family are, or if someone we like and admire says so. The inherent conflict between our desire to succeed, to be popular, and to be safe versus what we know to be ethically right is an age-old challenge. It requires courage. The novel’s themes of real dangers versus perceived ones; national security versus individual rights/privacy; racial profiling and labeling; book censoring; and hate-speech, hyperbole, or outright lying for political gain all seem startlingly relevant today.

We can learn from history—preventing heartache and disaster and war or devolving into small-mindedness and prejudices—if we read it, learn it, and heed it. I hope SUSPECT RED provides my readers an engaging story about friendship, family, loyalty, pack mentality, mistakes and their consequences, and the honor of personal integrity, while lending a telescope into a disturbing time in our history. Bottom line: I hope my readers come away committed to reading a variety of news accounts of current events and taking the time to tease out fact from rhetoric, in order to come to their own conclusions and choices. The most American thing to be is informed. The basic argument of our Revolution, after all, was that each human being has the ability to think, and, therefore, to govern themselves.

On March 9th, 1954, Edward R. Murrow and CBS’ See It Now ran “A Report on Senator Joseph R. McCarthy.” Murrow ended with these stirring words:

“The line between investigating and persecuting is a very fine one. . . .We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that accusation is not proof…

“[McCarthy has] caused alarm and dismay . . . and whose fault is that? Not really his. He didn’t create this situation of fear; he merely exploited it—and rather successfully. Cassius [from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar] was right. ‘The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.’”