[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Louisa June and the Nazis in the Waves ]

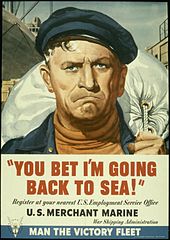

The Merchant Marine

Louisa June and the Nazis in the Waves

In the retelling of WWII, we tend to focus on the brave in battle—their heart-stopping tenacity, ability to think under fire, their fierce devotion to one another. We often forget those who transported—at huge peril—the armaments, trucks, medical supplies, and food that kept our soldiers, sailors, and aircrew alive. Their ranks include the Merchant Marines, men who worked cargo ships, freighters, and tankers that also supplied our cities and kept Britain on its feet, fighting Hitler, until we could deploy our troops to join them.

The seamen hailed from all over the nation: Boston, New York, Norfolk, Morehead City, and Miami, to name a few on the East Coast. Ten percent of the eventual 250,000 men serving during the war were African American, making the Merchant Marine the first racially integrated service. New recruits were trained quickly, including early morning exercises in cold waters, such as lowering rowboats or swimming underwater for a long distance, or jumping from a fifteen-foot tower into burning water to learn to “splash” their way to safety, away from an exploded ship and oil slicks set aflame.

One in eight of our merchant marines experienced his ship going down. They might have floated in frigid water or in lifeboats for days waiting for rescue. There were so many survivors of U-Boat attacks that the president of Boston’s Seaman’s Club founded the “40 Fathom Club” for survivors.

Many more died in explosions or burning oil slicks. Some were even machine-gunned by overly ardent U-boat crews as the sailors tried to make it to their lifeboats. Yet these civilian sailors still joined and re-upped. Their ranks quadrupled during the war as they stubbornly and defiantly delivered the critical supplies that kept Allied forces fighting.

The costs were high. In the end, 1,554 American merchant ships were sunk, and 9,521 mariners—one in 26—were killed, according to USMM.org (American Merchant Marine at War). Twelve thousand were wounded, 600 were taken as prisoners of war. All in all, our merchant mariners suffered the highest casualty rate of any service during WWII.

Even so, these men were not treated with the same respect other servicemen and women were. For instance, they were only paid when aboard a vessel––even if they were thrown into the water after a U-Boat attack, their pay was stopped until they were found, rescued, and back on another ship. As civilians, they received no health care, paid leave, pension, or money for college or low interest loans after the war. They weren’t even considered veterans or eligible for the Purple Heart Medal. Congress corrected this in 1943 by establishing the Merchant Mariner’s Medal, awarded to roughly 6,000 seamen. But it wasn’t until 1988 that they were finally labeled as veterans.

During the 1940s, the merchant mariners’ image was that of crusty ruffians, largely because anyone was allowed to serve, including “thieves and brawlers.” They were also viewed with some suspicion since Maritime unions might also accept communists, even though that didn’t reflect the political views of most members. As one Collier’s magazine reporter wrote, the reality of these men was often vastly different from public perception. Helen Lawrenson interviewed a gathering of them in a New York bar and described them drinking beer, singing sea ditties, and generally being gruff. But she also discovered them to be patriotic, fearless, widely traveled and cosmopolitan as a result, calling them among “the most truly sophisticated men” she’d ever met.

Sources:

https://www.loc.gov/vets/stories/cgmm-merchantmarine.html

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/merchant-marine-were-unsung-heroes-world-war-ii-180959253/

https://www.hrmm.org/history-blog/category/us-merchant-marine